What Is Linocut?

If you’ve ever heard the word “linocut” and pictured a woodcut, you’re already close. Linocut is exactly what it sounds like: a printmaking method where an artist carves a design into a sheet of linoleum, rolls ink onto the raised surface, and then prints that image onto paper.

And yes, it’s that linoleum, the classic floor-covering material, traditionally made from linseed oil mixed with cork or wood flour, pine resins, limestone, and pigments, pressed onto a jute backing.

What is linocut?

Linocut is a relief printmaking process in which an artist carves a design into linoleum, rolls ink onto the raised surface, and prints the image onto paper to create original, hand-pulled prints.

Unlike woodcut, linocut doesn’t follow the grain. The surface is smooth and consistent, which allows for fluid linework and intricate detail. That smoothness is part of what gives linocut its distinctive texture - crisp, highly detailed, and deliberate.

In this post, I’ll walk through what linocut is, how I make my prints, and why the medium itself shapes the final artwork.

Linocut vs Block Printing

(and why I care about the difference)

In recent years, “linocut” has been used as a catch-all term for carving any block, including the soft, rubbery block carving material that many beginners use. I dearly love the feel and look of printing with soft blocks, but prints from them are considered block printing. When I say linocut, I’m referring to carving actual linoleum. Not because I’m being precious about language (“precision of language,” as the mother reminds me in my favorite book, The Giver), but because the material changes the final work.

Linoleum is firmer than soft blocks like Speedball “speedy-carve,” which affects how it holds fine detail, how it responds to tools, and how the carved marks look once they’re inked and pressed onto paper. Simply put: different blocks produce different results. Soft blocks produce block prints. Linoleum produces linocuts.

A quick note on the word “print”

When people hear “print,” they often think of reproduction prints: a photograph of a painting, or a digital file printed in large quantities. But that’s not the kind of print that linocut produces.

Printmaking is a centuries-old process centered on creating multiple original impressions from a single carved block or plate. Even when an edition includes repeated images, each impression is still made by hand: the ink is rolled onto the block, the paper is placed, pressure is applied, and the print is pulled.

That’s why linocut prints are original fine art prints, not reproductions. Small variations happen naturally from print to print: slight shifts in pressure, subtle differences in inking, even small changes to the block over time. Those variations are one of my favorite features of the medium.

My point is this: though linocut prints are often priced lower than a painting, they live in a completely different category than mass-produced reproduction prints, because each impression is manually inked and printed. Linocut is one of the most accessible forms of relief printmaking, yet it demands a level of patience and precision that rewards slow, intentional work. They are valuable, original artworks, created in small quantities by artists around the world for hundreds of years.

How I make linocut prints

My process begins far from the studio, in the midst of daily life, where I’m always scanning for a scene I want to spend hours and hours carving.

I’m drawn to landscapes that interact with human-made structures: boats docked on water, a cabin tucked into trees, the reflection of a house on a still lake. I pay most attention to places that are familiar to me, like farmland on our regular family outings and the docks on the bay I grew up on.

From there, my printmaking process becomes a long sequence of small decisions.

1) Photograph

I gather images while traveling or moving through places I know well. Sometimes I find several subjects spontaneously in a single afternoon. More often, I notice them, hold them in my mind, and return later with a camera. That slow noticing is part of the work.

2) Draw

I use my iPad to translate the photo into a black-and-white drawing. This is my only digital step. The Procreate app allows me to capture extremely fine detail. This step is where I decide what will become inked and what will become light.

I work on a large digital canvas so that the drawn details can be very small. This is where the most decision-making is required, because it’s where I decide how the texture of each element in the scene will read in the final print. Skies and water are particularly challenging - and also, almost always, the most satisfying part of the final print.

3) Transfer the drawing to linoleum

Once the drawing is complete, I print it at the size I plan to carve (right now I’m loving 6x8 and 9x12). Then I transfer the image onto the linoleum using transfer paper and a fine pen. It’s a quiet, methodical stage that allows me to spend more time meditating and refining the full drawing.

4) Carve

Carving is the slowest part of my process, and the part I love most.

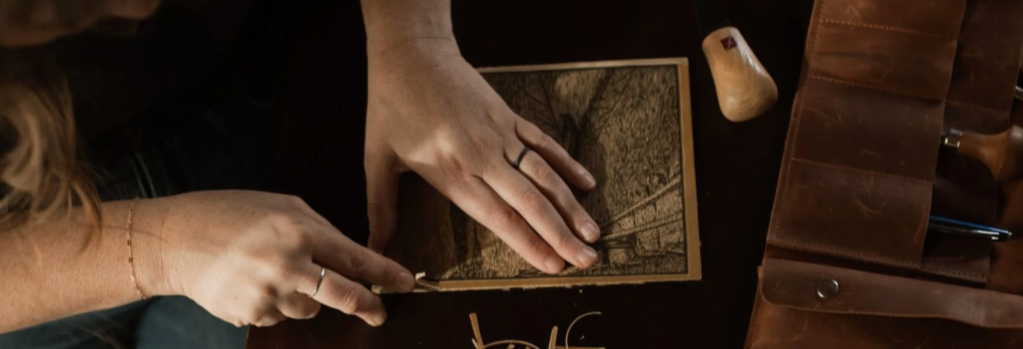

I start by carving the edges and major shapes, then move into the smallest details. I use micro tools (down to 0.5mm) for most of the carving to capture the finest of fine details, even in the larger prints.

The carving stage is also the most unforgiving: mistakes here cannot be undone. A slipped tool becomes a permanent mark. It becomes an unexpected flash of light in an area that was meant to remain dark. But I’ve learned to lean in and allow it when this happens. Those marks become part of the final image’s character, evidence of my hands’ involvement in the final piece.

5) Ink and print

When the block is carved, I roll relief ink onto the raised surface with a brayer, then print it on my press.

This stage is repetition at its best: Ink. Roll. Carefully place the paper. Roll it through the press with just the right amount of pressure. Pull the print. Repeat.

Though each print uses the same block and the same paper, they’re never identical. The act of printing is physical. It has rhythm. It’s another step that asks for patience, never speed.

6) Dry, title, sign, and edition

After printing, the prints dry on a rack. When each print is fully dry, I title, sign, and write the edition number. Then it’s sleeved, protected, and stored.

Why linocut is inherently slow

People often ask how long one print takes, and the honest answer is: it depends on what hours you count.

If you count only carving, an 8x10 block can take up to 20 hours, depending on the detail. If you include the drawing, the transfer, test prints, the final edition, and the drying time, it becomes a much longer arc of attention that’s closer to 30-40 hours from concept to finished edition.

If you include the time it takes to notice a subject in the world and recognize it as worth translating into carved lines, the timeline becomes its own season.

I don’t say this to romanticize the difficulty of linocut printmaking. I say it because linocut has a built-in refusal of urgency. The medium requires a pace that is slower than most of our days. And that slowness is the greatest gift.

Carving teaches me:

Silence and solitude are not optional; they’re practices that make careful work possible

Repetition can be restorative

Close attention changes not only what we see, but also how we live

Printing teaches me a different lesson: the rhythm of making isn’t separate from the meaning of the work.

The process shapes the outcome and it shapes the maker.

Why I chose linocut

I found carving in my mid-20s. Shortly after graduating with my Bachelor of Science in Psychology, I bought a stack of soft blocks from an art store on a whim. I was stressed and unsure of what would come next in my life, and I was looking for a way to quiet my mind.

Carving did that - and then it did more than that. It woke up a part of me that had been in hibernation since early childhood.

Since that day, I haven’t gone a single month without carving.

In the early years, I carved soft blocks to make hand-carved stamps, which opened up many incredible opportunities and eventually grew into a business, Modern Maker Stamps. But along the way, I realized I needed to protect the hand-carved work itself. I treasured that time too much to carve other people’s images for production. Since I still needed the financial support, I separated the rubber stamp business from my carving practice 10 years ago. But I never stopped carving.

Over time, block printing and linocut became the place where I could slow down and return again and again to my original intention: to make space for rest and quiet, and to spend time meditating on beautiful landscapes where earth and human hands meet.

What you’re buying when you collect a linocut print

When you purchase a linoprint, you’re buying the outcome of this slow, intentional process:

a carved block that required patience and precision

a hand-pulled print, made by hand, one impression at a time

subtle variation that marks the print as an authentic, original work

original artwork made to convey calm and retreat, both through the image and through the process that brought the subject to life

You cannot fake the kind of presence the linocut process requires.

The medium insists on space: in the studio, on the calendar, in the mind.

That insistence is not an inconvenience. It’s an invitation:

To choose work that asks for depth.

And to build days that can hold it.

That conversation about making space for what fills us up is one I’ve been sitting with deeply this year.

I’ll share more about that soon.

With love,

Sarah K

If we haven’t met, I’m Sarah K., an artist and writer based in Richmond, VA. From my sunroom studio, I create linocut prints and written blessings, shaped by quiet mornings and the rhythm of daily practice. My work centers on rest, stillness, and the beauty of everyday rituals.